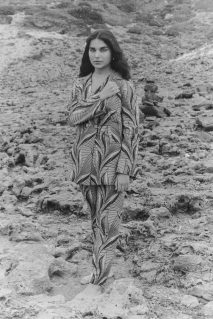

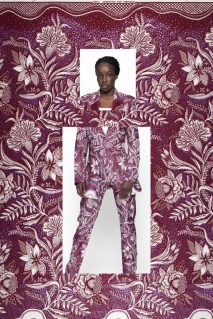

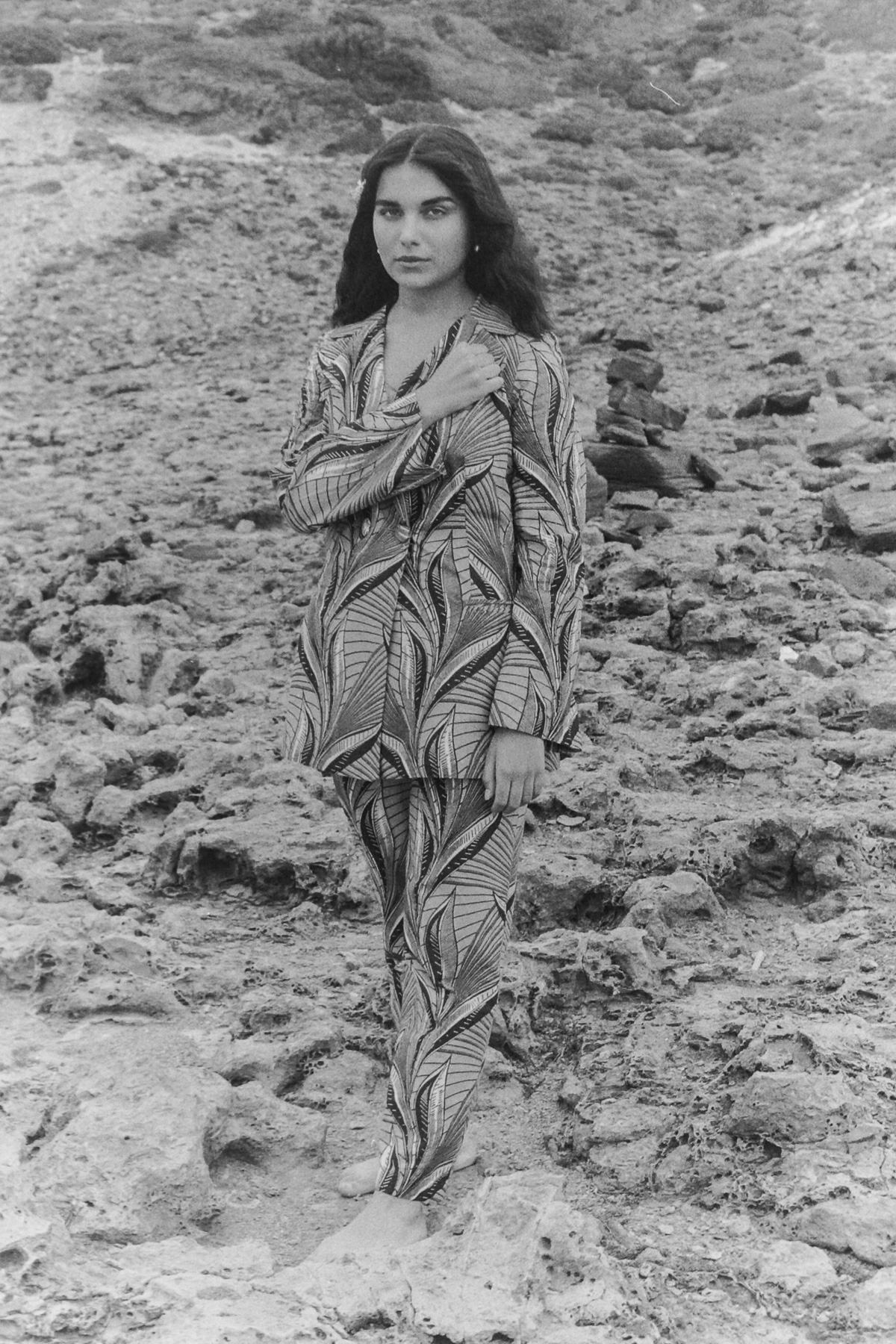

How Ghanaian women took the cross-cultural story of wax print to a whole new level.

Have you ever wondered what it would feel like to walk into a place and immediately communicate your message — without saying a word? African women have been perfecting the art of nonverbal communication, telling their stories through wax print clothing, for more than a hundred years.

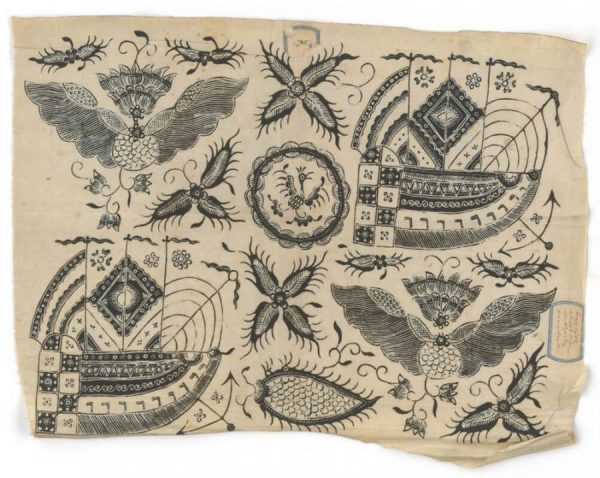

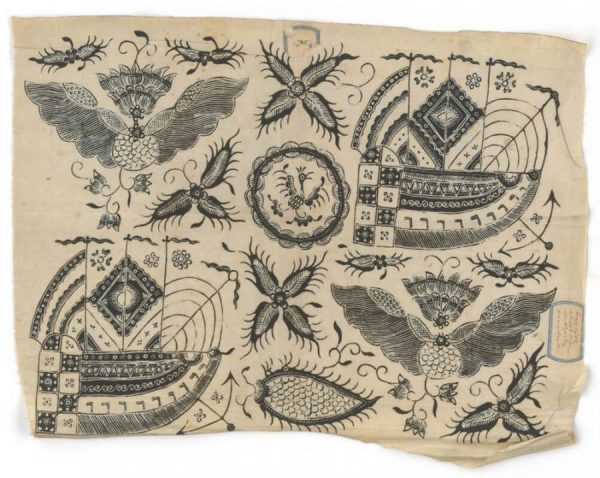

Originally produced in Holland and inspired by the batik designs and techniques of the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), wax prints have always had a thoroughly international artistic heritage — particularly when you add Indian-inspired British influences to the mix. But no sooner were they introduced into the African market in 1862 than African women made them their own, infusing them with African tradition and art.

These wax prints from Holland spoke the language of the women who sold them at the local markets in West Africa.

The prints first arrived in Ghana, and it was Ghanaians who masterminded this cultural evolution before it spread to the rest of the continent. The Makola market in Accra, where our name comes from, played a pivotal role in turning “Dutch Wax Print” into “African Print”.

At Maakola, we intentionally link garments to their social environment, where lies the beauty of our cosmopolitan DNA. Fashion is a vehicle that allows us to keep cultural phenomenon alive and celebrate the intertwining of different cultures. In addition to celebrating the Makola market in our name, we are a channel for we want to tell the West African women use their entrepreneurial skills to build an industry and an entire ecosystem revolving around the visual language, and, as a result, shape market forces between Europe and Africa.

The Makola market was the epicenter of the African fabric trade. Women working in the fabric stores created a background and story to any print, localizing it to resonate with their customers’ beliefs, traditions, and desires. As soon as fabrics arrived from the Netherlands, the saleswomen named them to reflect local sayings, with many prints acquiring a wide range of names as each market trader brought her own joie de vivre joie de vivre to a piece of fabric. Often named after notable personalities, events, places, or even sayings, wax prints became imbued with symbolism, and eventually gained the power to communicate a clear and emphatic message even while the wearer remained silent.