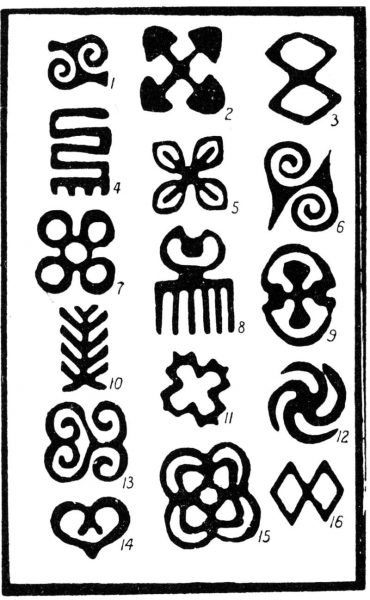

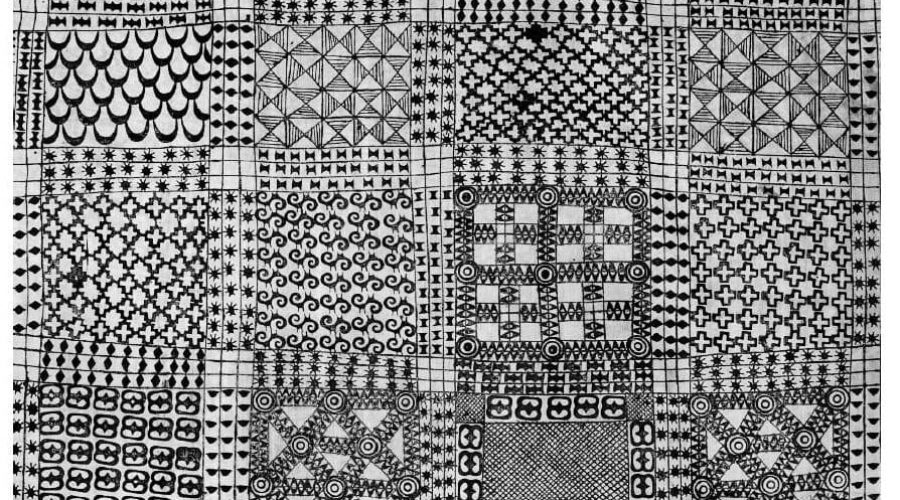

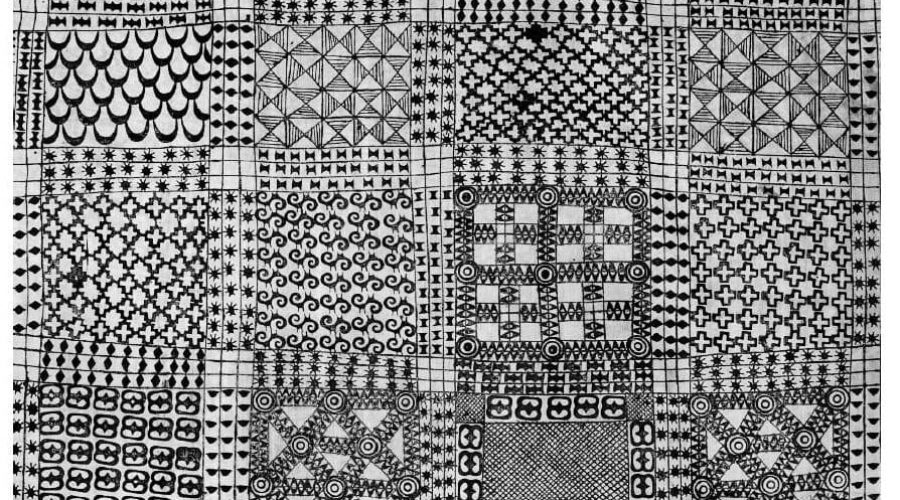

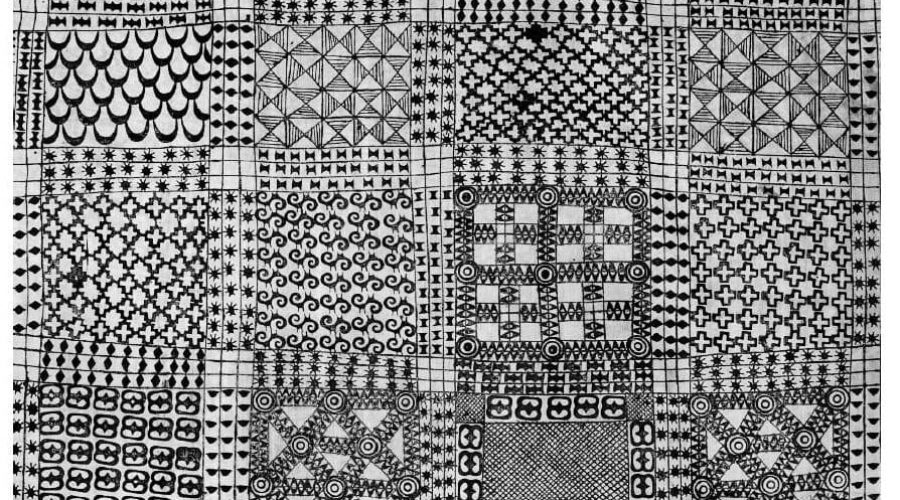

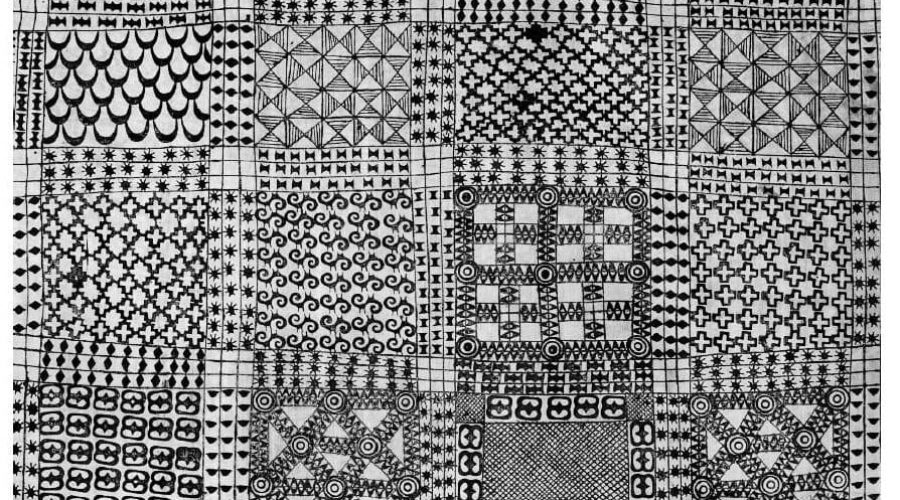

1. Gyawu Atiko, lit. the back of Gyawu’s head. Gyawu was a sub-chief of Bantama who at the annual Odwira ceremony is said to have had his hair shaved in this fashion.

2. Akoma ntoaso, lit. the joined hearts.

3. Epa, handcuffs. See also No. 16.

4. Nkyimkyim, the twisted pattern.

5. Nsirewa, cowries.

6. Nsa, from a design of this name found on nsa cloths.

7. Mpuannum, lit. five tufts (of hair). 8. Duafe. the wooden comb.

9. Nkuruma kese, lit. dried okros.

10. Aya, the fern; the word also means ‘ I am not afraid of you ‘, ‘ I am independent of you’ and the wearer may imply this by wearing it.

11. Aban, a two-storied house, a castle; this design was formerly worn by the King of Ashanti alone.

12. Nkotimsefuopua, certain attendants on the Queen Mother who dressed their hair in this fashion. It is really a variation of the swastika.

13 and 14 Both called Sankofa, lit. turn back and fetch it. See also

15. Kuntinkantan, lit. bent and spread out ; nkuntinkantan is used in the sense of ‘ do not boast, do not be arrogant ‘.

16. Epa, handcuffs, same as No. 3.

Adinkra symbols recorded by Robert Sutherland Rattray, 1927

When Dutch Wax Print first arrived in Africa, the designs featured symbols that are universal to all cultures, like plants and animals. However, designers soon started making more of an effort to introduce African design motifs, and started using indigenous textiles. By the 1920s, portraits of local community leaders and chiefs were being celebrated in wax print designs, as well as portraits of prominent politicians and African heads of state.

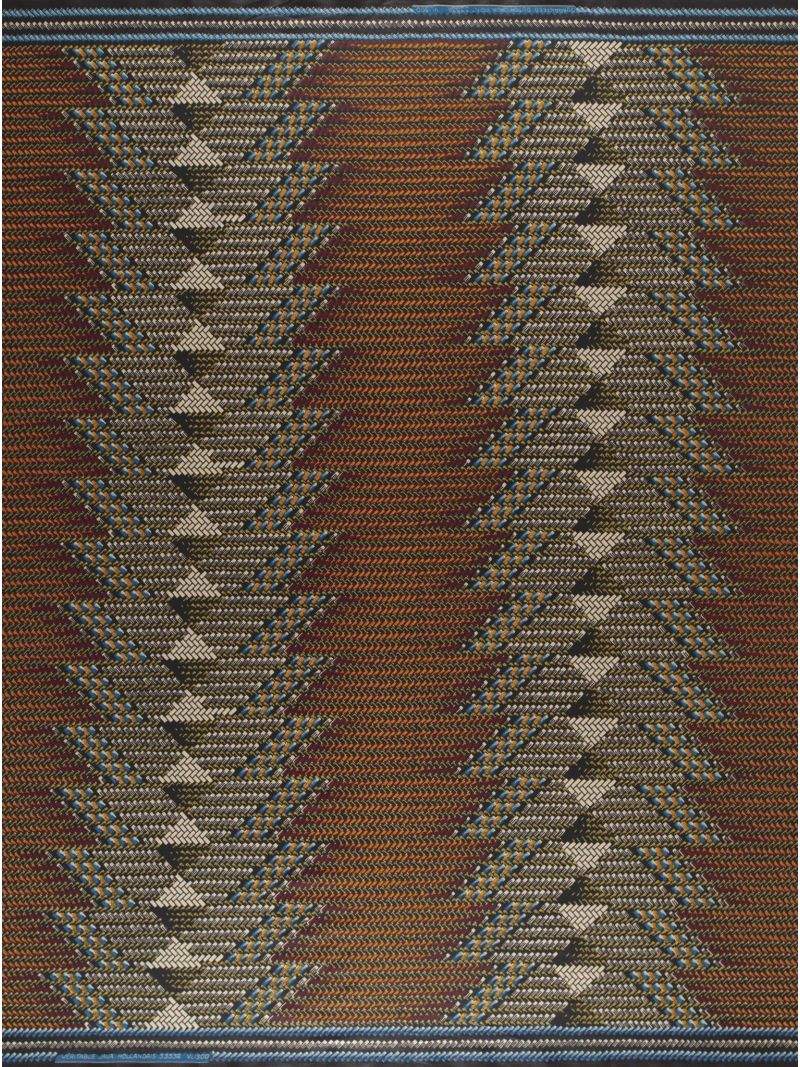

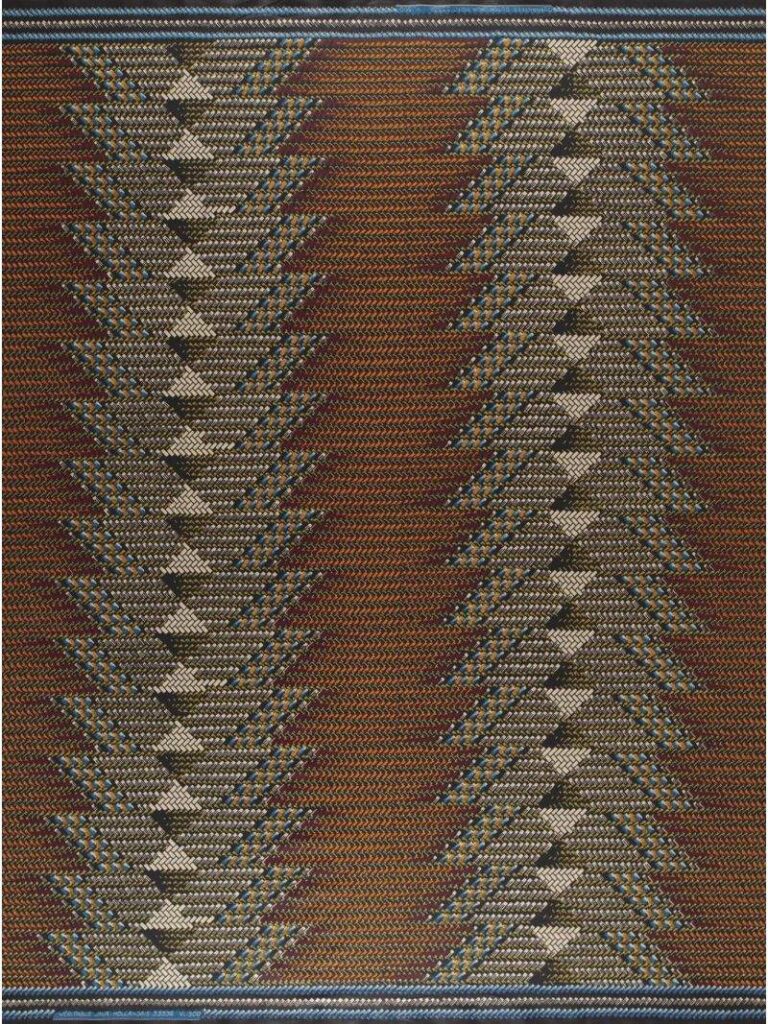

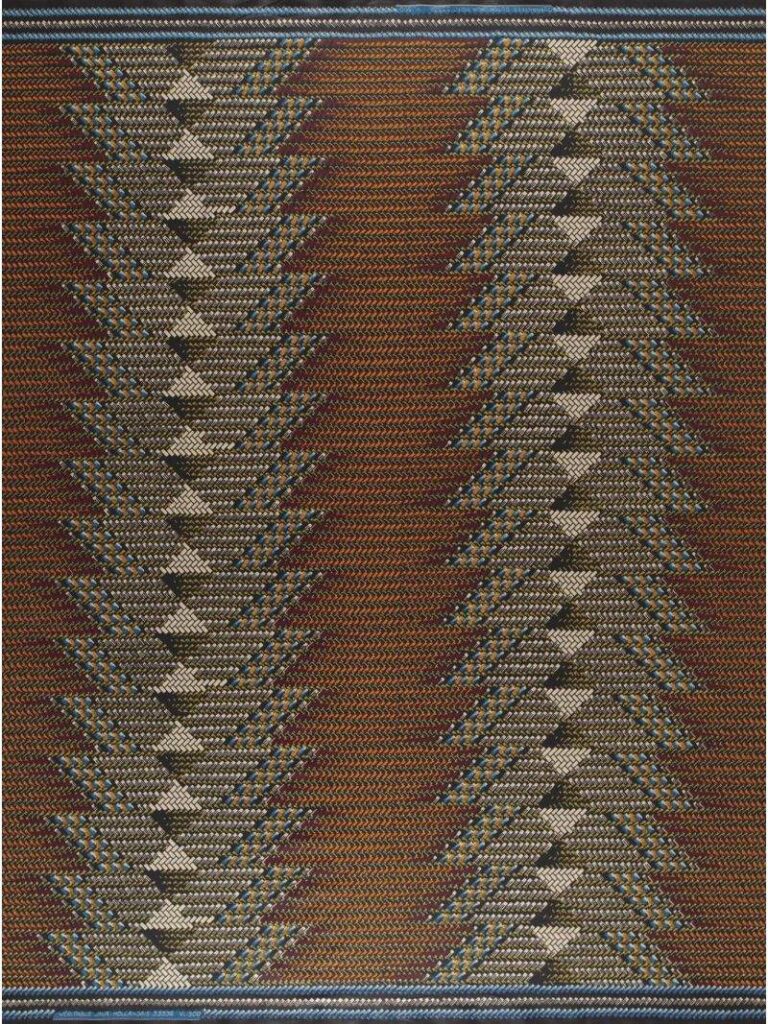

An example is the Ketapa, or Good Bed fabric. This geometric print features the Adinkra symbol for a mat in the background, symbolizing a marriage bed. This comes from the saying that if a woman sleeps in a good bed, then she has a good marriage.

“Kete Pa” Good Bed, Symbol of a Good Marriage.

From the expression that a woman who has a good marriage is said to sleep on a good bed. Contentment and fulfilment are two of some of characteristics of a good marriage. From the liberal translation, sleeping on your bed means all is well at home and you have a happy marriage.

Cloth as Metaphor: Symbols of the Akan of Ghana, 2Nd Edition By G. F. Kojo Arthur · 2017

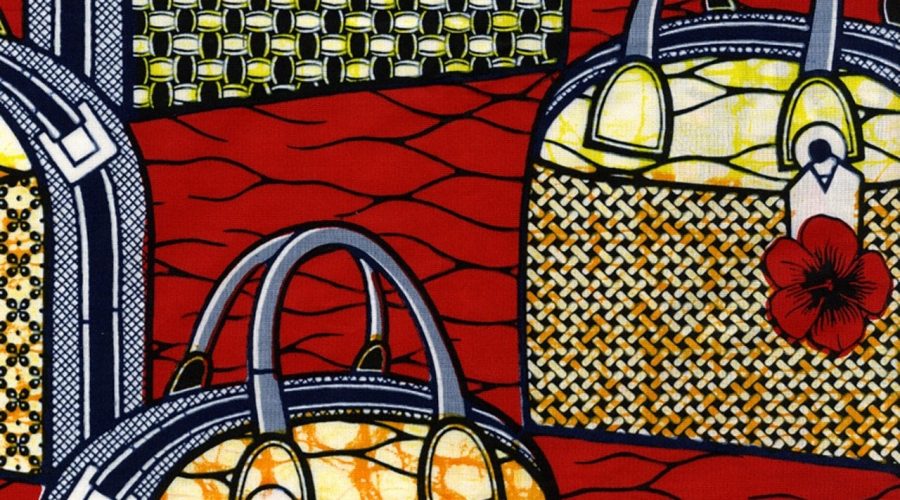

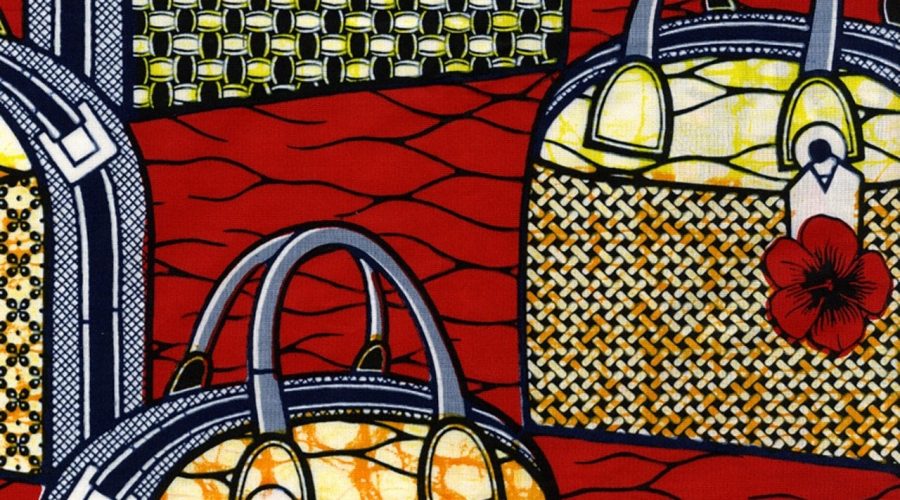

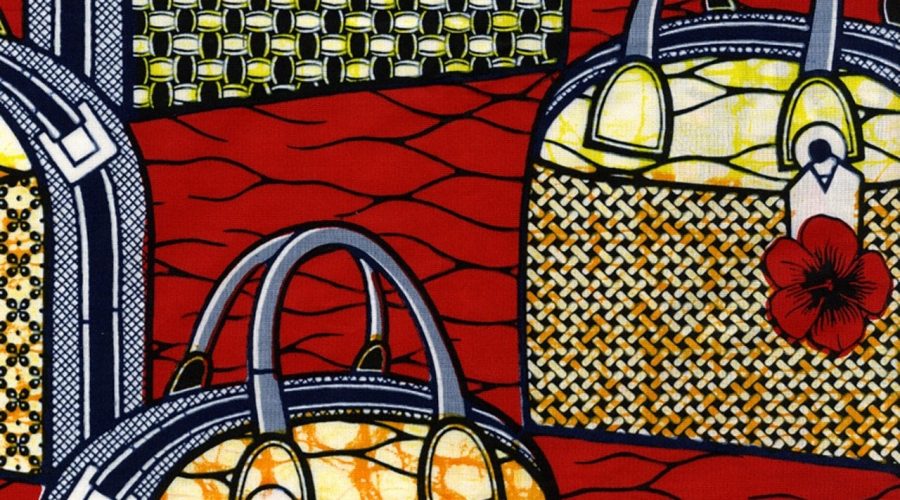

More recent events inspired the Michelle Obama’s Bag fabric. Featuring a vibrant print of, yes, handbags, this was released at the same time as the then First Lady of the United States arrived in Africa on a visit, and was pictured stepping off the plane with an eye catching handbag in tow.

In the same vein, the market traders of West Africa attached proverbs, slogans and catchy names to popular motifs, even if these names actually bore no relation to the designs on the fabrics.

For instance, a popular print of petal-like symbols that was designed in Holland can be appropriated to represent the beauty of happiness in a committed institution like marriage. Soon enough, a mythical story about the ability of the fabric to bring success and wealth to the wearer and their family becomes the norm. The fabric is then given a hopeful name like Fleurs De Mariage (Wedding Flowers) to reflect its marriage-healing abilities, or Rolls Royce for the great wealth it is believed to bring to the wearer.

Besides the patterns that are ascribed meaning when they reach the African trader’s shop, many wax prints are designed to reflect African culture. Here are a few of our favorites.

Si Tu Sors, Je Sors (You Fly, I Fly)

This print features open birdcages with both birds flying out. It is often interpreted to symbolize the release of newlyweds from their different homes into a life of love and support. But that same fabric, when worn by an indignant wife can be a not-so-subtle warning to her erring husband to mend his ways or be repaid in his own coin as she can ‘fly’ away too.

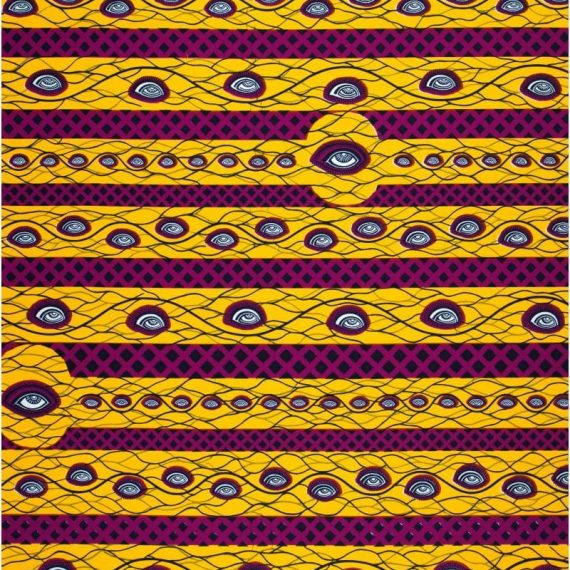

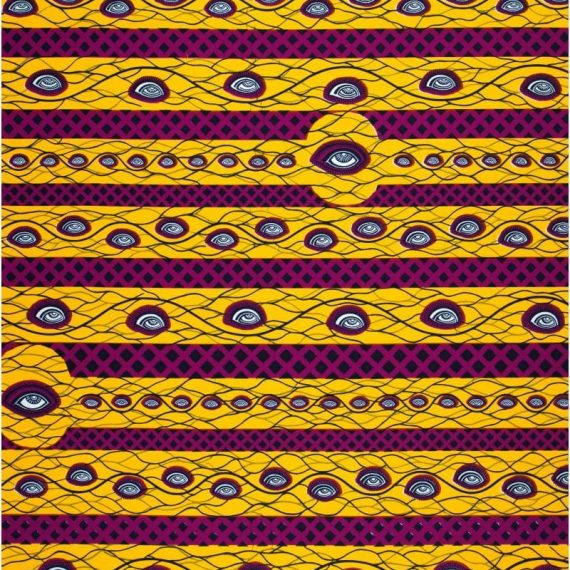

Eyes (or Lustful Eyes)

ABC

Educated people wear this popular fabric as a way of demonstrating their literacy. The print also serves the additional purpose of emphasizing the value of education.