In the first of our series about inspirational women, we pay tribute to the entrepreneurs of the Makola market — women who created an entire industry, and kickstarted a cultural conversation that continues to this day.

Inspired by the storytellers of the Makola market

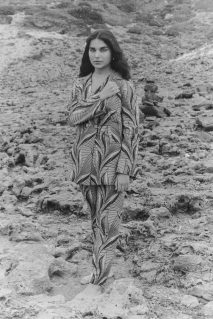

The women of Makola market open their stores at 6am, just when the sun is about to rise. They organize their fabrics, folding them neatly and piling them up one on top of the other, until they cover the entire wall of the shop. Eventually, you can’t see the color of the wall because the whole shop becomes a myriad of colors. The effect is hypnotic. It feels dizzying to walk into any of these stores, but as soon as you step in, you understand that you are not there to just buy a piece of fabric, but to build a relationship. You can easily spend an hour or more in store, losing track of time as the saleswoman tells the story behind each piece of cloth.

It has been this way for over a century. Makola market was established in 1924, and storytelling was central to the process of buying cloth. It was this tradition that first inspired Maakola’s founder, Aurora, to found her own fashion brand; each visit to the market drew her deeper and deeper into the world of African Print fabrics and their stories. In these fabrics, she felt a connection to the many people, over thousands of miles and hundreds of years, who contributed to their evolution. So when she founded Maakola, it felt right to pay tribute to the women of Makola market in our brand name.

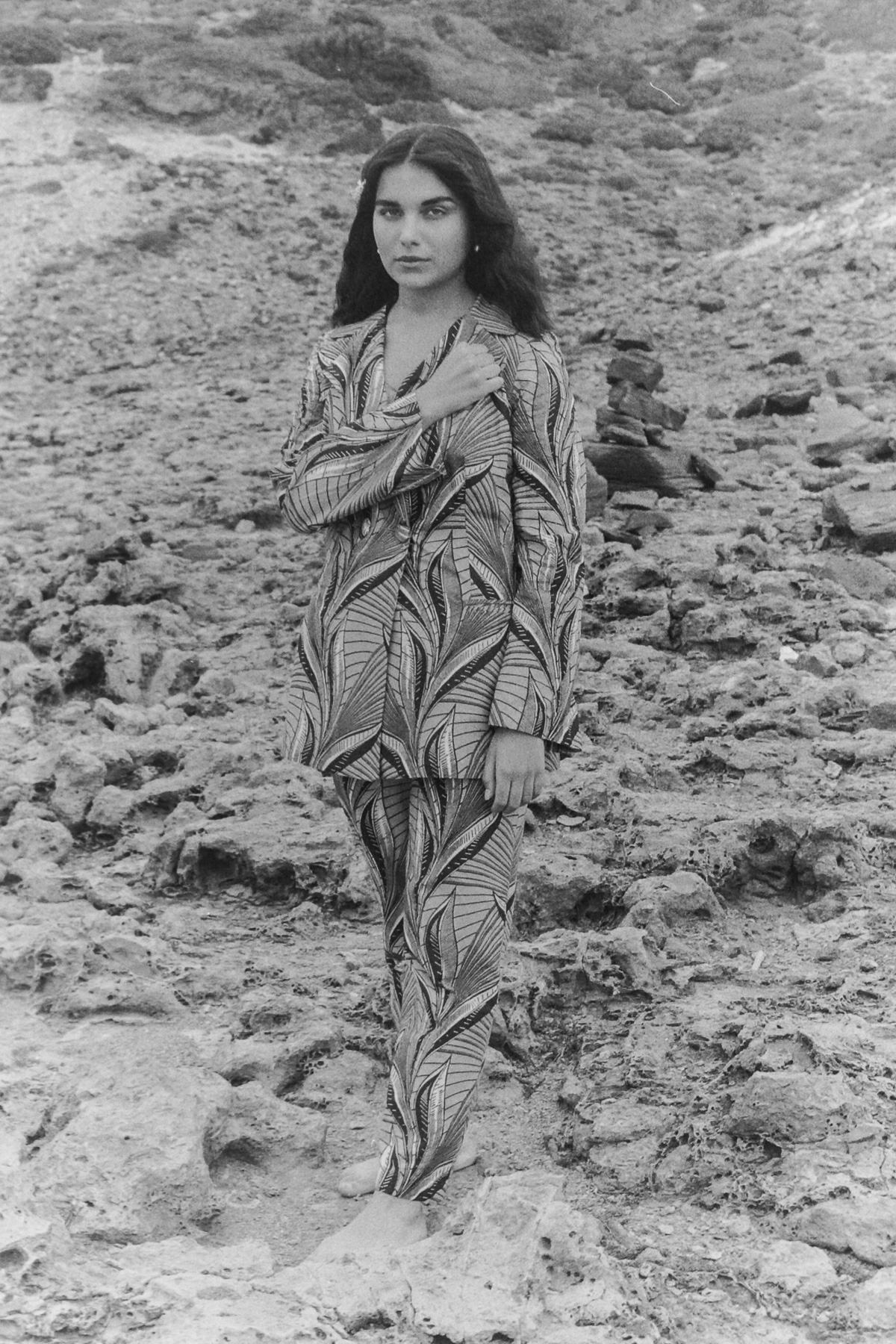

The women who started it all

We didn’t just want to acknowledge the Makola women of today. We owe a debt to the original fabric traders too. The enduring popularity of African Print fabrics is down to the women who first sold them, using the power of storytelling to drive demand and change the shape of the industry.

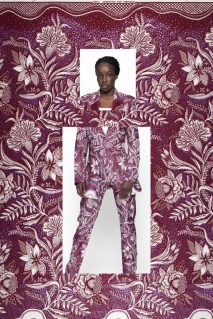

Dutch fabric houses first introduced their mass-produced wax prints — inspired by Indonesian batik — to the West African market at the end of the 19th century. African customers appreciated the small imperfections that characterized their first attempts at mass production, but this alone was not responsible for their success in the region. The fabrics became a cultural phenomenon thanks to the West African women who traded them.

These Wax Prints from Holland spoke the language of the women who sold them at the local markets in West Africa. There was already a long tradition in the region of assigning meaning to fabrics and clothes — Adinkra cloth, for example, was printed with motifs that symbolized sayings and proverbs. The saleswomen applied this tradition to a new vehicle with these Dutch fabrics, giving each print its own story as well as a new name that reflected their own culture. In doing so, they wove a West African tradition into the cloth, bringing the two cultures together.

Just as crucially, they began to influence the designs themselves. Alert to every shift in fashion and every small divergence in local tastes, these African saleswomen fed back to the fabric houses, essentially becoming co-creators. They were not passive consumers. They demanded change, and requested specific colors and symbols that would appeal to their customers. The first imported prints had featured plants and animals; gradually, bolder colors and geometric shapes appeared, and from the 1920s, the fabric houses began creating patterns featuring local leaders. Patterns such as “I fly, you fly”, imbued with local meaning, became best sellers.

What began as European expansion became a symbol of African culture, and an industry that employs thousands of people in Africa (Vlisco, for example, employs 1,650 people across Nigeria, Benin, Togo, Ghana, Ivory Coast and the DRC). These traders continue to inspire us today because they brought about real change. As we work towards a more sustainable fashion industry, it’s heartening to remember the women who changed the narrative a century ago.