Wax prints were made truly African through storytelling.

Africans didn’t simply adopt the Dutch fabrics but brought them to life, reversing the design process and shaping these prints to a West African aesthetic. More than distributors, the African women traders became co-designers. At Maakola, we hope to become a channel for West African women to share the story of their heritage and entrepreneurial skills.

How Our Prints At Maakola Continue The African Tradition

Wax prints are a way for West Africans to express themselves and create a rich cultural heritage for the people who wear them.

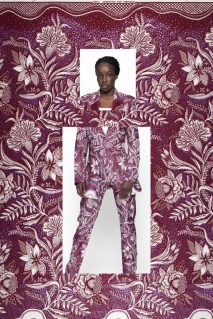

Now incorporating graphics that tell a story, from everyday objects like books and pens to art and pop culture references, African wax print resonates across the continent, from Nigeria to Ghana and South Africa. To celebrate this, every Maakola creation incorporates the local, traditional meanings imbued in each fabric, as well as our own, new stories — stories that communicate our values and beliefs, and honor the women we admire.

We see Maakola as a way to help keep the African print tradition alive and to extend it to the rest of the world, with fabrics that provide a vehicle for hundreds of women’s voices.

That’s why the fabrics in our collections don’t just tell their own story. At Maakola, we shape them into creations that share our own story, too — as well as the individual stories of the women who wear them.

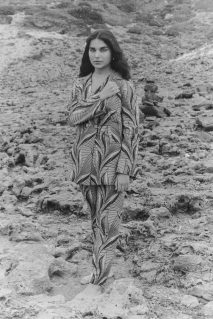

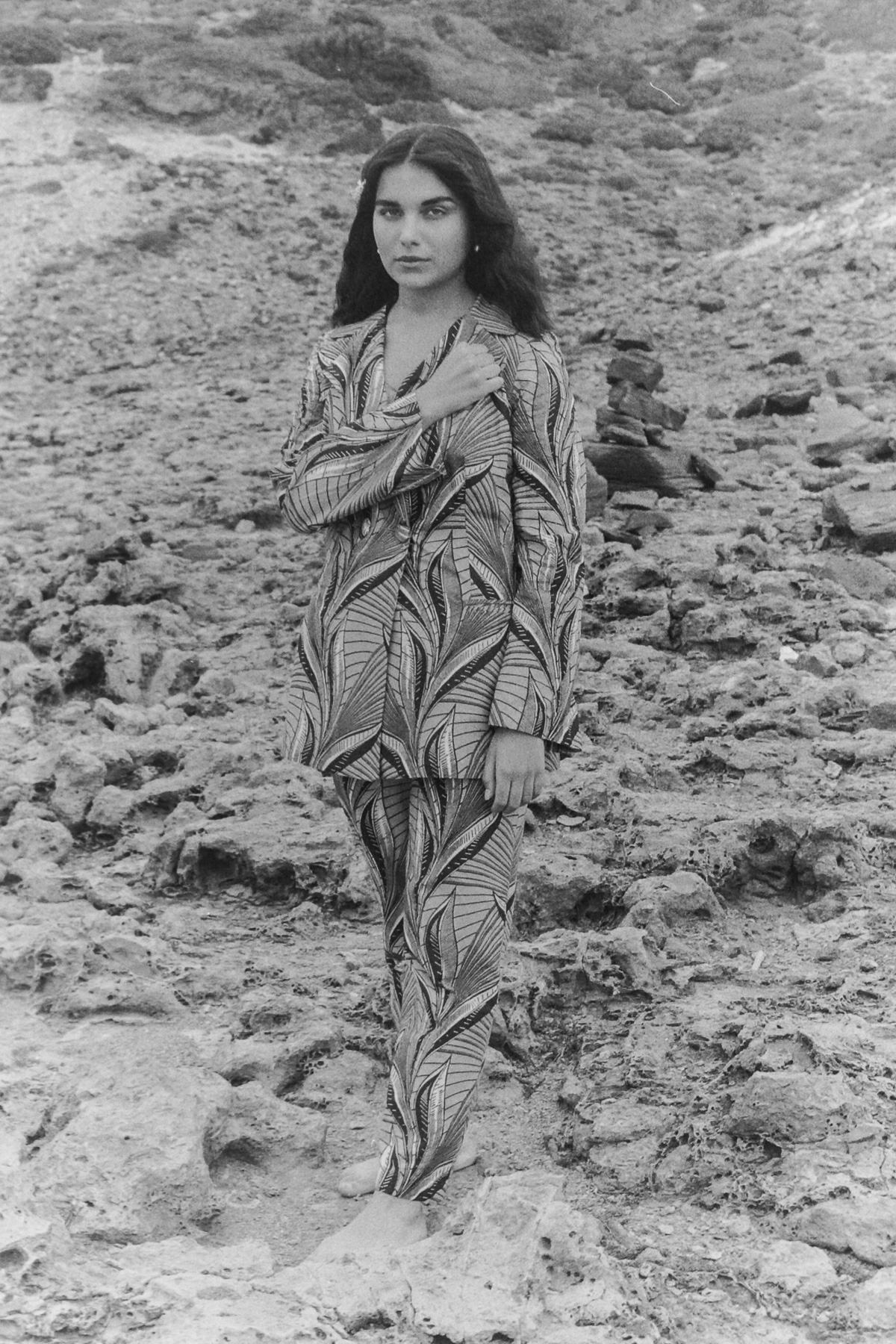

The Tree Of Life

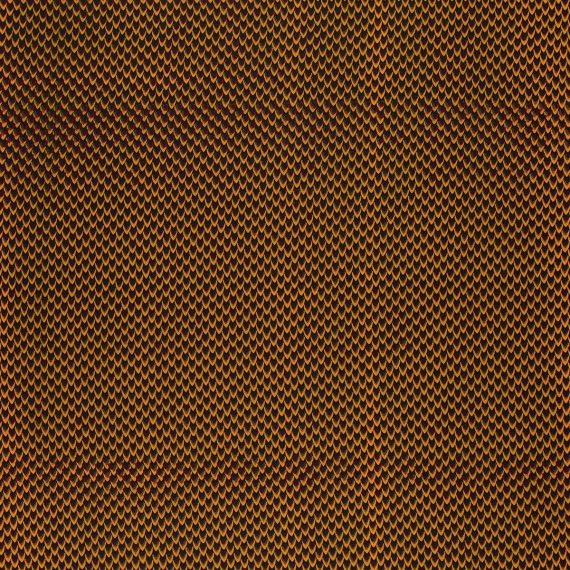

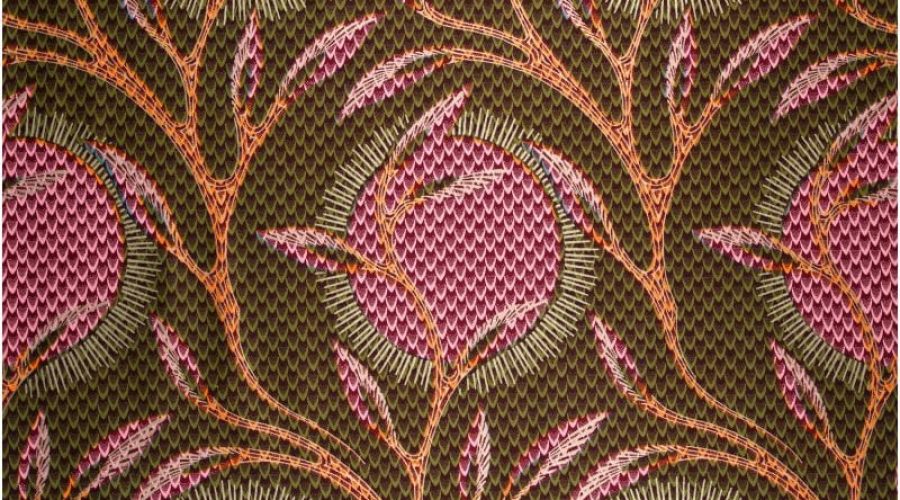

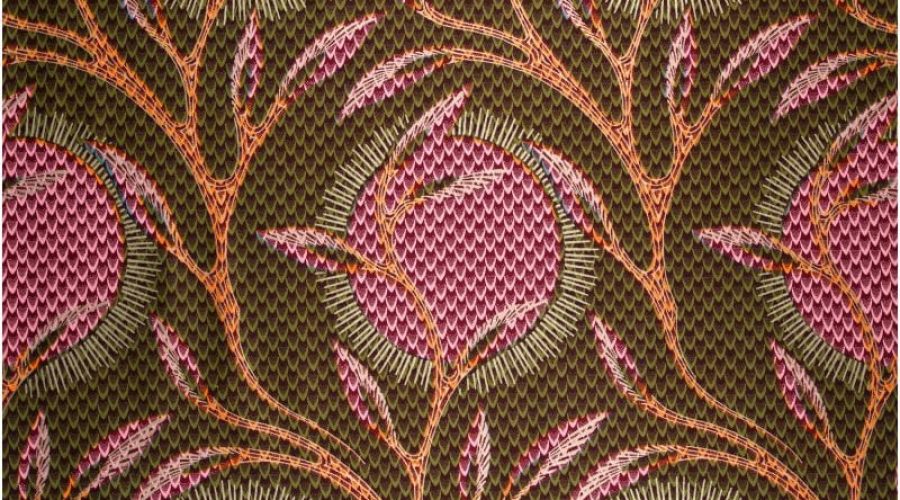

Most of the creations in the Gaia Collection come in the same wax print by Dutch fabric house Vlisco. Drawing on its rich heritage, Vlisco brought together two historical patterns, the Fish Scale and the Grotto, to create this new, modern cloth in fresh colors, with luxe silver and gold embellishments.

Fabric history: the Fish Scale and the Grotto

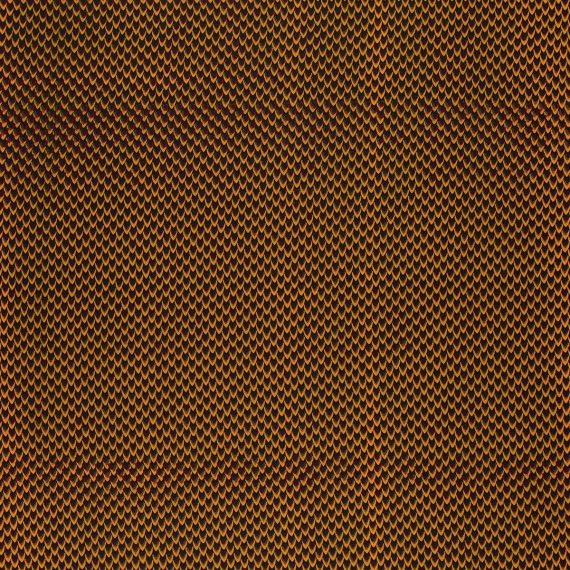

The Fish Scale

This print is known by many different names across African tribes. Perhaps the most popular is Akpirikpa Azu, a direct translation of its English name by the Igbo speaking people of Eastern Nigeria. The name is inspired by its scale-like pattern, with yellow fish scales adding repeating pops of color to a fabric that generally comes in shades of brown.

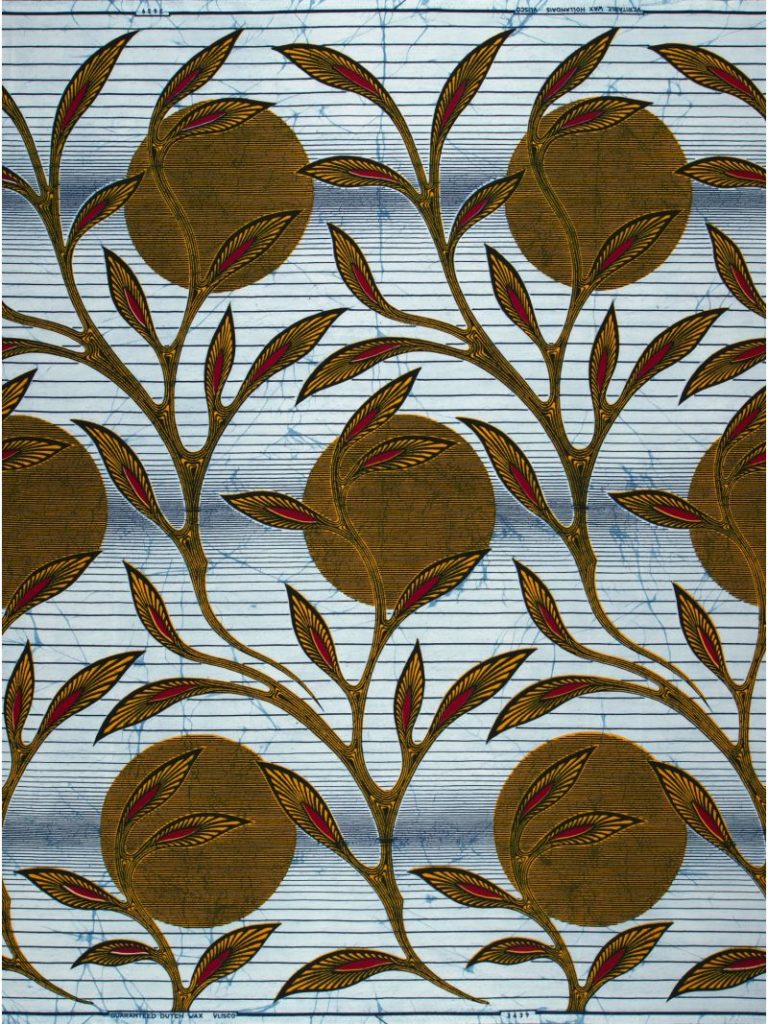

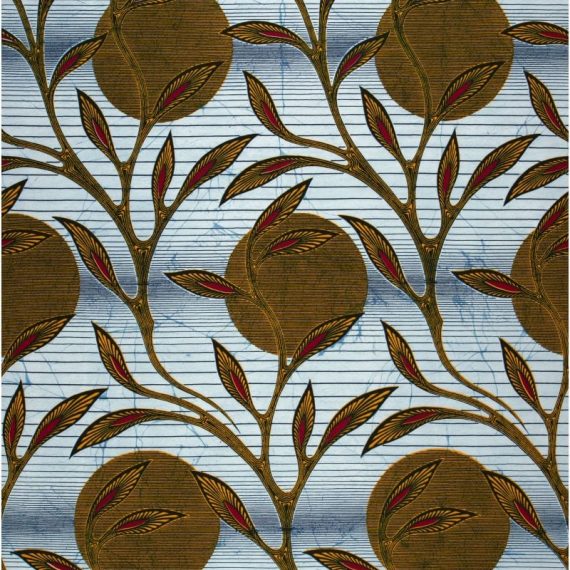

The Grotto

This second fabric is usually worn in affirmation of a woman’s social status. The term “grotto” refers to a wealthy person who is well recognized socially. This name comes from the Côte d’Ivoire, where the fabric has been used in the country’s traditional pagnes (rectangles of cloth that wrap around the body) for generations. But to the Ghanaians, this same fabric means something else entirely: in Ghana, it is a reminder of the innate ingratitude of human beings. Ghanaians call it Papa Ye Asa which directly translates to “goodness is finished”. The Grotto features round discs and swirling leaves on a contrast background.

The Maakola meaning: The Tree of Life

To us, this pattern represents the Tree of Life: the connection between all things in the universe. This print reminds us that our lives depend upon the environment — something that we as humans often forget. But we are always connected to other creatures and plants, and we can see this in the pattern. Deeply embedded in the ground, the roots of the Tree receive nourishment from Mother Earth, while its branches rise to the sky, receiving energy from the moon and sun.

The combination of the Fish Scale and the Grotto suggests interconnected trees with their full buds, set against a luminous sun. It creates an image of immortality and rebirth: The branches grow and blossom every time there’s a new sun behind them. The contrast of the sun makes the new buds appear full of life, like fresh leaves unfurling in the spring. Between one sun and the next, we can see a hibernation phase that always ends with a new sun and the beginning of a new life. The Tree of Life also symbolizes the immortality of Mother Nature because even as a plant grows old, it continues to create seeds that carry its essence so that it can live on through new saplings.